Even if one has little knowledge of the history of photography, it is likely that Dorothea Lange’s iconic image known as Migrant Mother will be familiar. It is one of the most recognizable photographs of the 20th century. Initially, and for many decades, the image represented the desperation of ordinary people during the economic woes of the 1930s. With its resonant echoes of Christian iconography, Lange’s Migrant Mother became a symbol of compassion, of how progressive documentary photographers, by witnessing tragedy and injustice, could employ “a camera with a conscience” to change the world for the better. More recently, Lange’s photograph has been reevaluated in terms of the ethics of representation and the presumptions and limits of “concerned photography” in general.

The National Gallery of Art’s reassessment does not shy away from this discourse. But more importantly, this exhibition reframes Lange’s 50-year career in terms of portraiture, of her fundamental empathy for human beings and her extraordinary skill at constructing images that not only vividly describe individuals but capture, in gesture and atmosphere, the material, political, and psychological realities of her subjects.

Born in Hoboken in 1895, Lange was a restless and curious child who was struck with polio, leaving her with a limp and a vital sense of empathy for her entire life. An early fascination with photography led Lange to seek an apprenticeship with the well-known New York society photographer Arnold Genthe, whose soft-focus Pictorialist images Lange found lovely but empty, although Genthe’s influence is obvious in her earliest portraits. She moved to San Francisco and set up her own photography studio in 1918 and was soon associating with an extraordinary group of artists and photographers, including Anne Brigman, Imogen Cunningham, Consuelo Kanaga, Tina Modotti, and Edward Weston. It was in this aesthetically and politically progressive milieu that Lange developed her approach to “expressive portraiture,” to use Imogen Cunningham’s phrase.

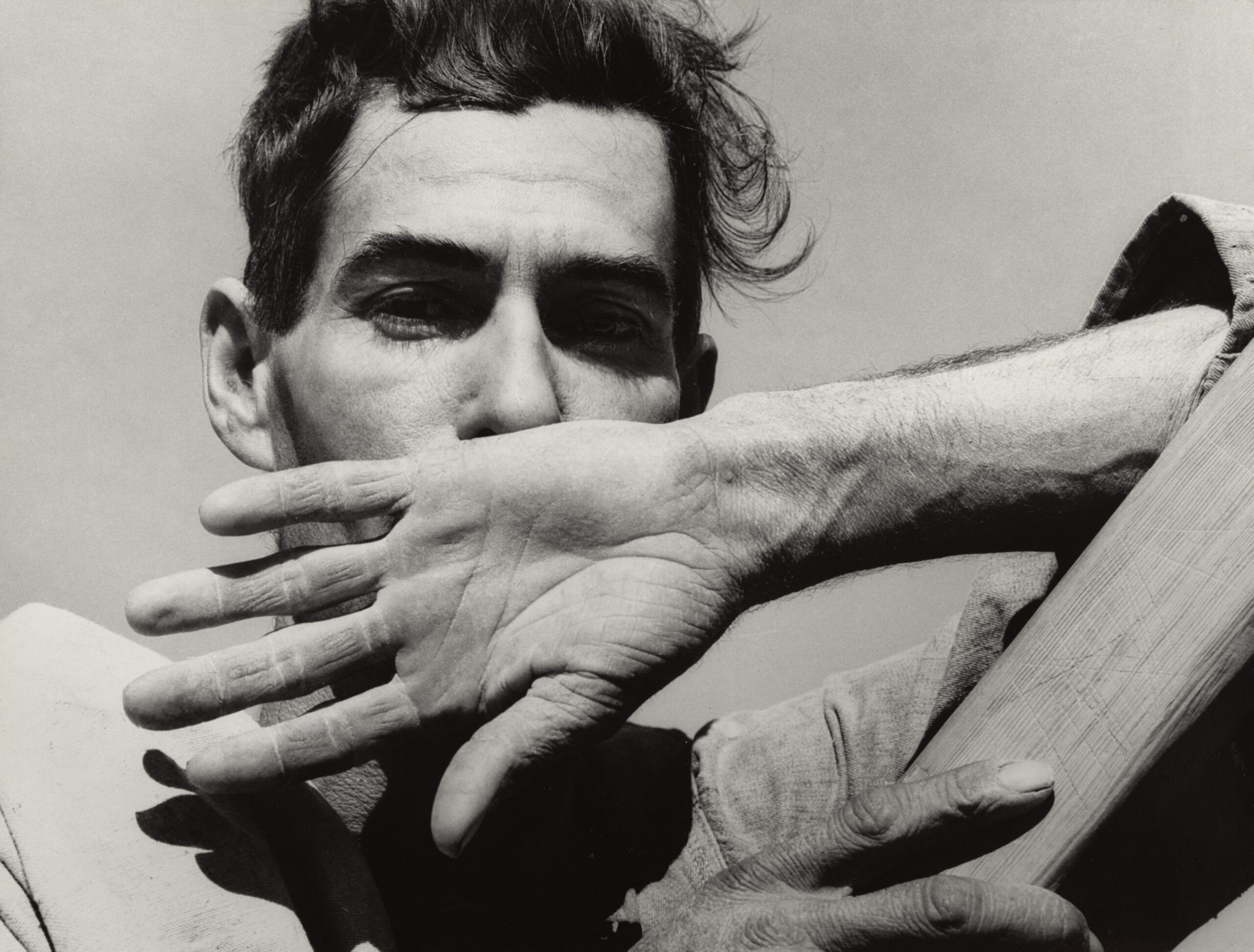

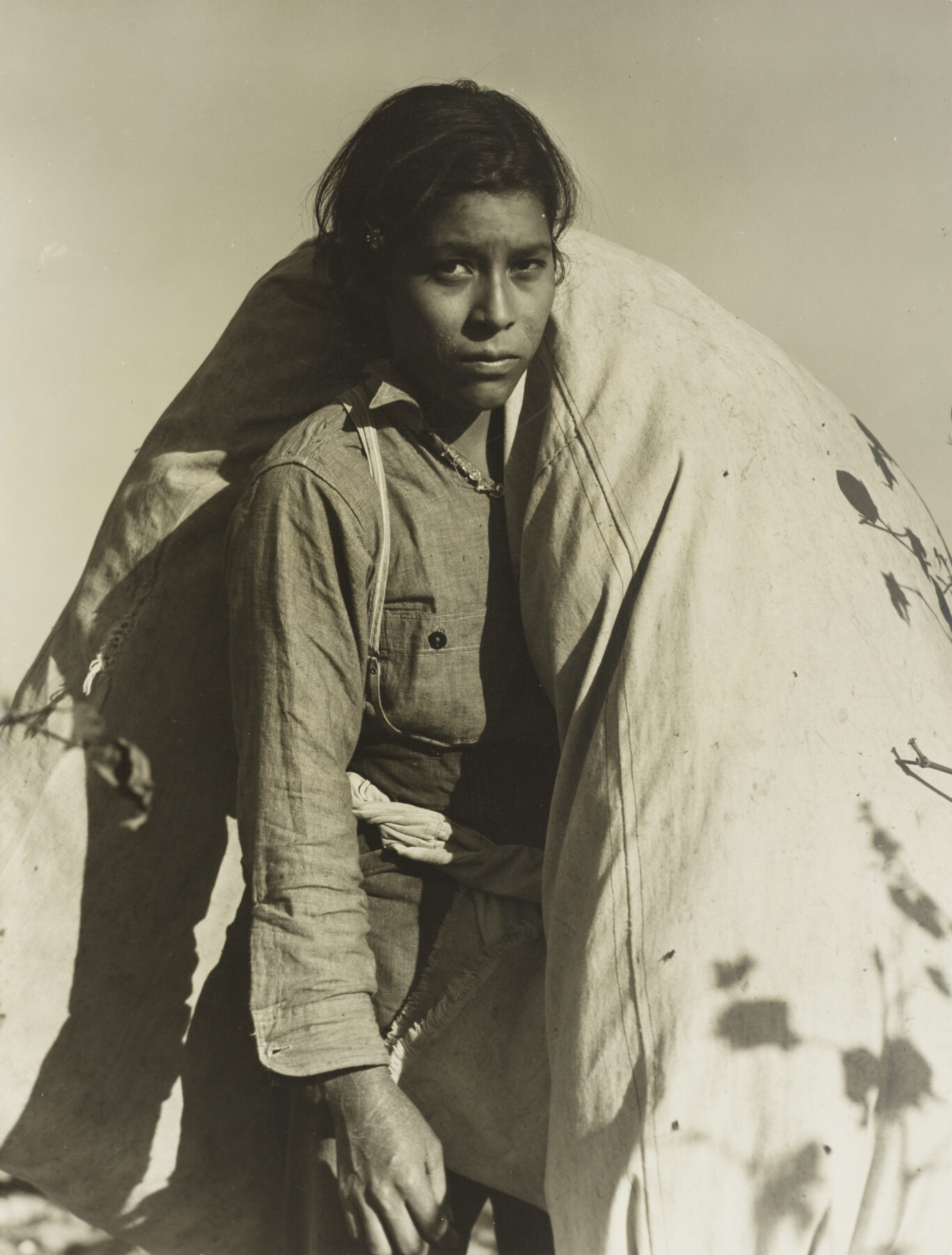

In the early 1920s, she married the painter Maynard Dixon and traveled with him extensively in the Southwest. During this period, she shed her Pictorialist tendencies to make images of Indigenous Americans that employed sharp details of faces, hands, and body parts, an approach that informed her practice thereafter. Even before she was employed by Roy Stryker and the WPA, the economic and political tumult of the early 1930s led Lange to begin documenting the desperation and upheaval on the streets of San Francisco. Some of her most well known and affecting images are from this period, including White Angel Breadline (1933) and May Day, San Francisco (1934), which shows a young woman clutching an armful of socialist periodicals while listening intently to a speech.

Lange’s work could be viewed as a dialectic between the idea of the masses and the specificity of the individual. Many of her images employ hands as signifiers of work, prayer, devotion, connection, and despair. She was sensitive to the quieter, but no less charged, moments of sharecroppers, dock workers, and the unemployed. Many are hauntingly beautiful, such as Young Cotton Picker, San Joaquin Valley (1936), in which a full and apparently heavy sack of cotton drapes over the shoulder of a young worker whose beautiful defiance transforms his burden into a regal cape. With 100 images, ranging from the 1920s to the 1960s (Lange died of cancer in 1965), this exhibition generously and brilliantly demonstrates that Lange’s legacy extends far beyond the symbolic limitations of Migrant Mother and that her empathic photographs are a profound gift to the visual archive of the 20th century.