One stormy night in 1816, while staying at Lord Byron’s villa near Lake Geneva, an 18-year-old woman tossed and turned in the thunder-filled darkness. Her name was Mary Shelley, and she was having a nightmare about a monster made from scraps of humans.

Frankenstein, the novel Shelley would fabricate from her vision, is regarded as a fable of science gone wrong. Yet it is also a rumination about art. Victor Frankenstein, the monster’s creator, is as much sculptor as scientist. Like Pygmalion, the sculptor from Greek myth, he makes a body and it comes to life. And what is this monster but a collage? A full century before the likes of Kurt Schwitters and Georges Braque, Shelley seems to have presaged every modern artistic discipline that sticks together fragments of the world, from collage to photomontage to assemblage art.

In 1818 – the year Frankenstein was published, making this year its 200th anniversary – Lord Elgin’s haul of sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens had just been installed at the British Museum in London. They caused a sensation and placed the idea of physical perfection very much in people’s minds. But these finely honed bodies were of no use to Shelley. She gives us instead a living statue that has no harmony, no easily discernible form, no beauty. As soon as Frankenstein sees his creation, he is horrified. “Great God!” he cries. “His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath.” The disgust is not moral but aesthetic.

It wasn’t that Frankenstein didn’t set out to create beauty. He selected a beautiful face and kept all of the limbs in proportion – albeit on a colossal scale, for the creature was eight feet tall. Yet somehow the result was hideous. In contrast to Pygmalion, who falls in love with his creation, Frankenstein loathes his handiwork.

Our protagonist made his monster while studying natural sciences at Ingolstadt University in Bavaria, yet his labours and their result have little in common with the researches of any scientist in Shelley’s day. Creating life? Medicine had yet to find basic ways to preserve it. This was the age before antibiotics, and Shelley was well aware of the inadequacy of medical science. Ten days after she was born, in 1797, her mother died from a post-partum infection.

The mad experimenters of the Romantic age, the people who really did seem able to create life from dead things, were not scientists. They were artists. Braving the anatomy theatre and the mortuary to study the human body, they transformed this dark knowledge into throbbingly vital art.

The year Frankenstein was published, a young French painter named Théodore Géricault started a stupendously ambitious work that he planned to unveil at the Paris Salon the following year. It was to be more than seven metres across. Géricault had been looking around for a suitable theme, and settled on the shipwreck of the Medusa, a French navy ship that cast away dozens of people on a makeshift raft after the vessel ran into trouble off the coast of west Africa in 1816. There were dreadful battles aboard the raft and some resorted to cannibalism. To prepare himself, Géricault headed for the morgue.

Anatomy was considered vitally important for artists. George Stubbs had dissected horses, hanging their carcasses from the roof of a barn in Horkstow, Lincolnshire, peeling off layer after layer of tissue to perfect his racehorse paintings. His endeavours are evident in the title of the book he produced: The Anatomy of the Horse, Including a Particular Description of the Bones, Cartilages, Muscles, Fascias, Ligaments, Nerves, Arteries, Veins and Glands.

Like Stubbs, Géricault reasoned that to paint a truly extraordinary work of art, he had to delve deep into anatomy. Hence his scavenging around the morgue. In fact, at times Shelley’s muscular prose could almost be describing Géricault. Like Frankenstein, the painter “pursued nature to her hiding places … collected bones from charnel-houses and disturbed, with profane fingers, the tremendous secrets of the human frame”.

Géricault’s research is captured in a series of perversely voyeuristic paintings he made of these “anatomical pieces”, a leg here, an arm there. He eventually joined these body parts together to create something thrillingly macabre: his monstrously powerful painting The Raft of the Medusa, which created just the sensation he hoped for at the 1819 salon. The lost souls are depicted in a desperate moment of hope: the survivors are signalling to a distant ship on the horizon, surrounded by the dead, the dying and the dismembered.

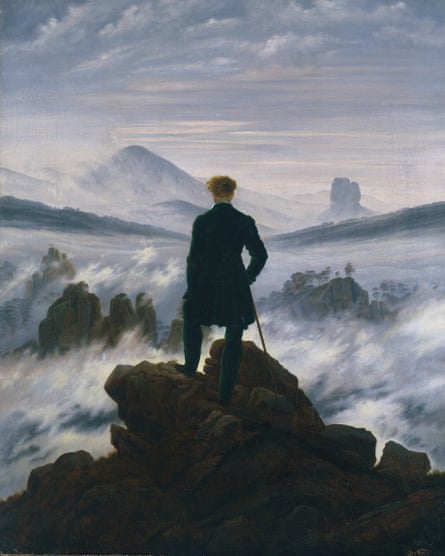

Géricault was not the only artist pushing his vision to dangerous, Frankensteinian extremes as Shelley’s novel hit the bookshops. In Germany, Caspar David Friedrich painted icy wastes, desolate shores and deathly ruins that generate a terrifying sense of nothingness. The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, painted in 1818 or just after, is a bone-chilling image of a solitary hiker brooding over a sublime void. It is uncannily reminiscent of Frankenstein’s contemplation of an alpine glacier: “For some time I sat upon the rock that overlooks the sea of ice. A mist covered both that and the surrounding mountains.”

But can any of this compete with the terrifying masterpieces of Francisco Goya? The painter bought a house outside Madrid and started covering its walls with murals depicting witches, mass delusions and a dog drowning in quicksand. Begun in 1819, Goya’s 14 horrifyingly brutal Black Paintings defiantly assert the freedom of art to think what it likes, to be what it likes, however dismal and despairing. It’s an assertion as bold as that of Frankenstein sculpting with the dead.

Is the similarity between these conjurors of horror and Shelley’s monster-maker a coincidence? It is not. The writer had an intimate knowledge of the characters and methods of Romantic visual artists. It was part of her inheritance as the daughter of a revolutionary. Her mother was Mary Wollstonecraft, whose 1792 manifesto A Vindication of the Rights of Woman took apart prevailing attitudes to gender and reminded her fellow radicals in the age of the French Revolution that it wasn’t enough to keep banging on about the rights of man.

Less well known is that Wollstonecraft was also a pioneering Romantic, whose passion for art got her entangled with a painter whose morbid imaginings paved the way for the likes of Géricault, Friedrich and Goya. Henry Fuseli came from Switzerland – where Frankenstein resides – and seized the imagination of 18th-century Britain with his gothic fantasies. The most unforgettable is The Nightmare, in which a grotesque demon perches calmly on the midriff of a woman stretched out in sleep. This evocation of the power of dreams was painted in 1781, long before Sigmund Freud and the surrealists “discovered” the unconscious. Freud would later keep a copy hanging in his apartment in Vienna.

Wollstonecraft had a deep feeling for art, according to Shelley’s father, the radical thinker William Godwin. After his partner died at the age of 38, Godwin wrote a tell-all biography of her titled Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman. He needed the cash. He makes it very clear that Fuseli, and not himself, was the man who most fascinated Wollstonecraft. Art, he recalls, gave her “exquisite sensations of pleasure”. Consequently, she was exhilarated to meet Fuseli, who was in turn thrilled to encounter someone so “susceptible to the emotions painting is calculated to excite”.

It was a meeting of minds, and Wollstonecraft was soon in love, despite the fact that Fuseli was older and married. Did he live out his fantasies through art? In his erotic drawings, he repeatedly depicts a man being pleasured by two women. Wollstonecraft knew Fuseli was never going to leave his wife, and her longing became, says Godwin, “a source of perpetual torment”. The only way she could break the spell was to flee to revolutionary France, where she tried to forget Fuseli amid the swoosh of the guillotine.

Shelley couldn’t escape this gothic love story. It was there for her to read in her father’s memoir. One striking passage in Frankenstein seems to have come straight from Fuseli’s brush. After the shock of seeing his monster come alive, Frankenstein decides to have a lie-down. He goes to sleep, as if hoping everything will be all right when he wakes. Instead, he has a nightmare, in which the creature stands over him. “I beheld the wretch – the miserable monster whom I had created. He held up the curtain of the bed; and his eyes, if eyes they may be called, were fixed on me.”

This visitation is unmistakably reminiscent of Fuseli’s The Nightmare. The painting even has a red velvet curtain, which is parted like Frankenstein’s, in this case to reveal a ghost horse with dead eyes.

It was the artist who broke her mother’s heart who provided Shelley with her image of the manic Romantic creator. Perhaps her novel is as vengeful as the monster who punishes Frankenstein for his selfishness by killing everyone he loves. Frankenstein may share many features with the great Romantic painters of his day, but there’s one crucial difference: he is a bad artist. His arrogant belief in his creative powers is deluded. When it comes to creating life – and beauty – he simply has no talent.

Godwin encouraged his daughter’s own feeling for art, taking her to studios including that of JMW Turner. But painting, like making a monster, was a man’s job. So Shelley wrote her creature into being instead. You could see Frankenstein as a failed Romantic artist who accidentally invents something new, whose value he cannot see. It is an art of scraps, a found art that has no godlike absolute creator, but is instead assembled from pieces of the existing world.

In a fabulously violent image, the German dadaist Hannah Höch described her photomontages as being “cut with the kitchen knife”. In her 1930 work German Girl, she creates a grotesque yet likable face from cut-out fragments: a monster who has made herself.

The pieces of Shelley’s brilliant creation will never stop reassembling themselves.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion