In 1969, when I was nine, Stan Lee seemed as good as any writer I’d read. Sure, I could tell that his tendency to puff a Fantastic Four script as “a pulse-pounding pastiche of philosophical profundity” was over the top. (The “p” in “philosophical” wasn’t a proper alliteration, for a start.) But the claim of profundity was well founded, wasn’t it? At the climax of the aforementioned Fantastic Four story, a crazed ex-Nazi underling of the dictator Doctor Doom aims a flamethrower at a dissident in a hall full of looted paintings. “My life is of little consequence,” pleads the dissident, “but this art – it is irreplaceable!” “Art? What do I care for art??” yells the ex-Nazi, just before being killed by Doctor Doom, who, it turns out, values art over human life. My nine-year-old brain may not have contained the term “ideological complexity”, but here it was.

When asked to name his favourite authors, Lee always included Shakespeare. He certainly had fun injecting faux-Shakespearean flavour into his story titles: “If This Be Doomsday”, “If The Past Be Not Dead … ”, “Lest Tyranny Triumph …!” and hundreds more, festooned with ellipses and exclamation marks. (The Bard’s own “Oh, What a Tangled Web We Weave … ” was a must for Spider-Man.) He was, as he once said, “really big into the rhythm of words … The way the words string together impresses the hell out of me.” He also loved the phraseology of the Bible. By presenting young readers with high-flown vocabulary and classical allusions beyond their grasp, he made his pulp fictions seem more grown-up than they really were.

Lee could write in many registers. He pioneered superhero comics’ engagement with what was going on in the real world, whereas the comics published by Marvel’s arch-rival DC were typically set in imaginary places such as Gotham City and Smallville where nobody was politicised, homeless, oppressed or troubled. In sharp contrast to the inhuman vacuity of Superman, Lee’s superheroes were plagued by anxieties, ambivalence and a messy interface with an imperfect world. In mid-60s Marvel comics, not only did Vietnam exist, but American soldiers got blinded there and students on Spider-Man’s campus protested against the war. The X-Men, always needing to hide their mutant nature from a general public fiercely prejudiced against them, embodied a neat antisemitism metaphor (both Lee and his co-creator Jack Kirby were Jewish). Typical of Lee’s socially progressive ethos was his inclusion of black characters as articulate, much-valued members of communities, workplaces and – eventually, with the advent of Black Panther in 1966 – the superhero pantheon.

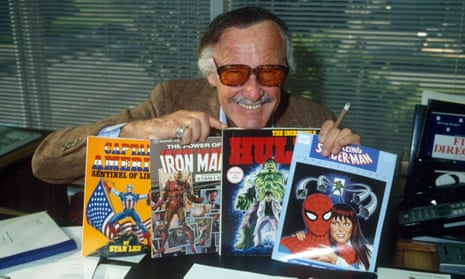

By the 1970s, as comics readers grew older and more sophisticated, Lee handed over the scripting duties to a new generation, who brought increasing maturity, pretension, cynicism and ultraviolence to the storylines. If Lee felt any unease about this, he never showed it. Latterly excused from any literary duties, he relished his role as the company’s PR dynamo, lecturing at colleges and pitching ideas to Hollywood. A smooth negotiator, he managed to get very rich from the Marvel corporation while Kirby – who invented or co-invented some of the characters that currently rule our multiplexes – was apparently overlooked.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion