"I was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1943," says Larry Clark in the introduction to Tulsa, his now iconic photobook from 1971. "When I was 16, I started shooting amphetamine. I shot with my friends every day for three years and then left town, but I've gone back through the years. Once the needle goes in, it never comes out."

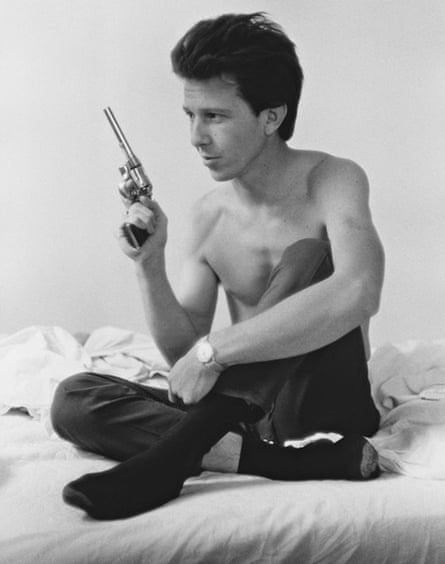

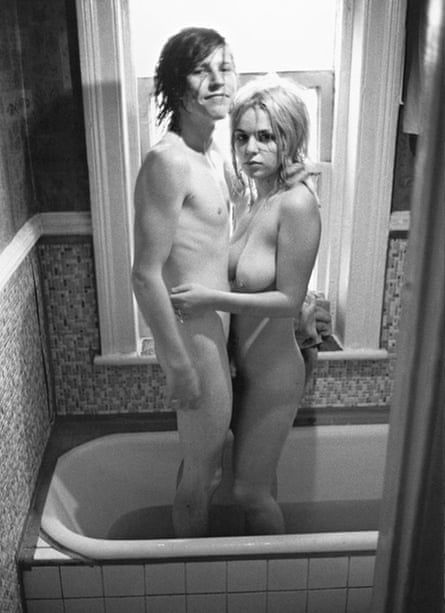

Tulsa remains Clark's most visceral book, an insider's view of a period in the mid-1960s when he was a teenager living what he calls, without irony, "the outlaw life" – shooting up speed, having sex with his strung-out girlfriends and hanging out with his gun-toting junkie friends. Sex, drugs and violence were captured in a raw, grainy monochrome that defined the raw confessional style adopted later by Nan Goldin, Corinne Day and Antoine D'Agata. But Clark went there first, and Tulsa remains a template for all that followed, a blurring of the lines between voyeurism and intimate reportage, between honesty and exploitation.

Writing about Tulsa in The Photobook Volume 1, authors Martin Parr and Gerry Badger say that the "incessant focus on the sleazy aspect of the lives portrayed, to the exclusion of almost anything else – whether photographed from the 'inside' or not – raises concerns about exploitation and drawing the viewer into a prurient, voyeuristic relationship with the work." Yet it is that very dynamic that imbues the images with such disturbing power.

Next week, Foam in Amsterdam pairs images from Tulsa with photographs from Clark's follow-up, Teenage Lust, for a show that reminds us just how unsettling Clark's early vision of the teenage "outlaw life" was, and remains. Clark's long-lost film, Tulsa, which was shot in 16mm in 1968 and rediscovered in 2010, will also be screened – an altogether more experimental precursor to the movies that followed, including Kids and Ken Park, and full of graphic sex.

The film, like the photographs is, as Clark once told me, "a record of his secret teenage life." When he first saw the prints, he was as shocked and scared as everyone else. "I remember thinking, 'I have either got to burn all the negatives and shoot myself, or go down to LA and try and get it published.'"

But the subsequent publication of the book and his reputation as a groundbreaker did nothing to appease his demons. Because of his subsequent heroin addiction, it took Clark 10 years to complete Teenage Lust, which was finally published in 1983. An autobiography of his teenage years, it comprised more raw images of drug use and adolescent sex, as well as portraits of young hustlers working Times Square in New York, with a little of the edginess leavened by family snapshots and portraits. (Intriguingly, his mother was a studio photographer who specialised in mother-and-baby portraits.) It is a more thoughtful book, but it also prefigures Clark's seeming obsession with the wayward lives of teenagers, which has since become the central theme of his films, most controversially Kids, and later books like 2008's Los Angeles Vol 1, in which he trails a bunch of skater kids from Compton, east Los Angeles. Here, the early black-and-white vérité style is replaced by a lingering, brightly-hued gaze that sometimes looks like a street-fashion shoot. It seems a long way from Tulsa.

There was no judgment, no moral point of view in his early work: these kids all look like they're simply having a good time, as they shoot up or point guns at one another. But they still disturb viewers today because of that – and because they depict suburban America; this wasn't a blighted inner-city picture, but the kids next door.

One of Clark's images, of a young girl grinning as she gleefully squirts liquid from a syringe, has never left me. He was more instinctively sure of himself when he was young and actually living what he was photographing, even as his doggedly self-destructive life spiralled out of control. Tulsa, for all its voyeuristic charge, was made in extreme circumstances by a driven young man whose life lurched from one drama to the next: intravenous amphetamine use at 16, a brief spell in art school in New York at 18, a two-year stint in the US army in Vietnam, and a return to Tulsa at 20, where he lived with a prostitute and graduated to heroin.

When I pushed him on why he was so self-destructive, Clark fell uncharacteristically silent, then mentioned his abiding feeling of being ignored and unloved by his father as a child. A classic Freudian drama, then, played out in extremis by a lost boy who, for a long time, was intent on self-obliteration. And yet he survived, like Nan Goldin after him, by picking up a camera and shooting the chaos of his crazy life – even as he wanted to do anything but that. "When someone I knew would die, which happened a lot, I'd think they were one of the lucky ones," he told me. "I honestly used to think I was cursed to stay on earth and make photographs."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion