Shall we then, at last, discuss Jae Lee?

He’s been around for a fair while, our Mr. Lee. He started really young - not even 20 years old when he got his start on a Beast serial in Marvel Comics Presents that ran concurrent to Sam Kieth’s breakout Wolverine feature, 1991. Kieth's was the trippy serial that immediately followed Weapon X and somehow managed to not stink up the joint. A fairly high-profile gig for both artists. Oh, and Lee’s credited co-penciler for the first two parts of that serial? Rob Liefeld, incidentally.

Then they put Lee on Namor, penciling in place of John Byrne. Now, in the interest of honesty, I must say: at the time I dropped the book like a stone two issues into Lee’s run.

Ugh, I know. I was too young to be so partial to John Byrne. Certainly not so much to drop a book I liked because he stopped drawing it. But when I was a kid? Just did not get it. Namor was among my very favorite books for the first couple years of its existence - especially the first year, where Byrne really committed to using a lot of Duo-Shade. And in fairness, those are some of the best-looking comics he ever produced. But Duo-Shade on every page was fairly labor-intensive, it couldn’t last forever. Byrne's second year on the book saw the end of the Duo-Shade, and his third year saw the advent of Jae Lee.

Can you see how, by the sheltered standards of 1992, my reaction at least made sense? I get it now, of course. Lee's Youngblood: Strikefile and WildC.A.T.s: Trilogy (both 1993) are some of the most remarkable-looking comics from their era. Lee was unique in his cohort and age group for taking more after Bill Sienkiewicz than Art Adams or Walt Simonson - perhaps a proclivity accentuated by necessity, given the number of comics he produced over a very short time period in the early '90s. He’d figured out how to build compelling narratives around surprisingly sparse pages and indelible, exaggerated figure work. More than anyone else this side of Gilbert Hernandez, Lee isn’t afraid of leaving empty space on the page.

Still to this day, Lee is the master of the sparse composition. He can also do many other things, but the image you see in your mind when you think Jae Lee is a high contrast color palette built around isolated images that take up half the page or less. He’s a great cover artist for precisely that reason; he can arrest your attention from across the room because he isn’t afraid to to go stark raving minimal.

The interesting thing about those sparse panels - not just good for action. Also really good at communicating silence and quietude. I'd caught up with Lee by 1998, when he and Paul Jenkins did Inhumans for Marvel Knights - the only time I’ve ever really cared for the Inhumans concept and thought it could support its own weight in a book. That was a talky series - lots of simmering conversation and verbal back-and-forth. Changed my view of the man’s work forever. What I’d missed the first time I saw him was the exquisite understanding of form. Often his figures seem like marble - not an affect of journeyman stiffness, but a care of composition and precision of gesture that leans classical. Classical as statuesque.

Over the decades, Lee’s line has evolved into something far more delicate. The closest comparison I can find is in Lee’s precise contemporary Paul Pope. There’s a similar purposeful tentativeness in their lines, something that recalls a more mature iteration of Tony Salmons’ diaphanous mid '80s style. Very rare to find any manner of solid bold line in a Jae Lee comic book.

Lee doesn’t do as much interior work as you’d hope. He does a lot of covers, as I said. It’s news when he stops by to do interiors. A quick glance at his bibliography betrays the fact that his longest acquaintance with a series was 23 issues of the Marvel adaptation of Stephen King’s The Dark Tower, 2007-10. Marvel did more Dark Tower comics than you probably remember, from a period where the only outside licenses they pursued with any vigor were literary titles such as this and the Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter series. For what it’s worth, Ron Lim drew more issues of sexy vampire hunter Anita Blake than Jae Lee drew of Roland Deschain. But not by as many as you might think.

In all that time he never returned to creator-owned work; not after his initial foray with Hellshock in the mid '90s. Like Seven Sons, that was an Image series interested in saying a few words on the subject of organized religion. Of course, Lee isn’t actually the owner here - the legal indicia for Seven Sons ascribes the copyright to Robert Windom, who writes the series with Kelvin Mao. Windom's page on the Image website indicates he’s an attorney and screenwriter, with no other completed comics work. If that’s the case, I’d say the guy got extraordinarily lucky to debut his comics writing career with Jae Lee.

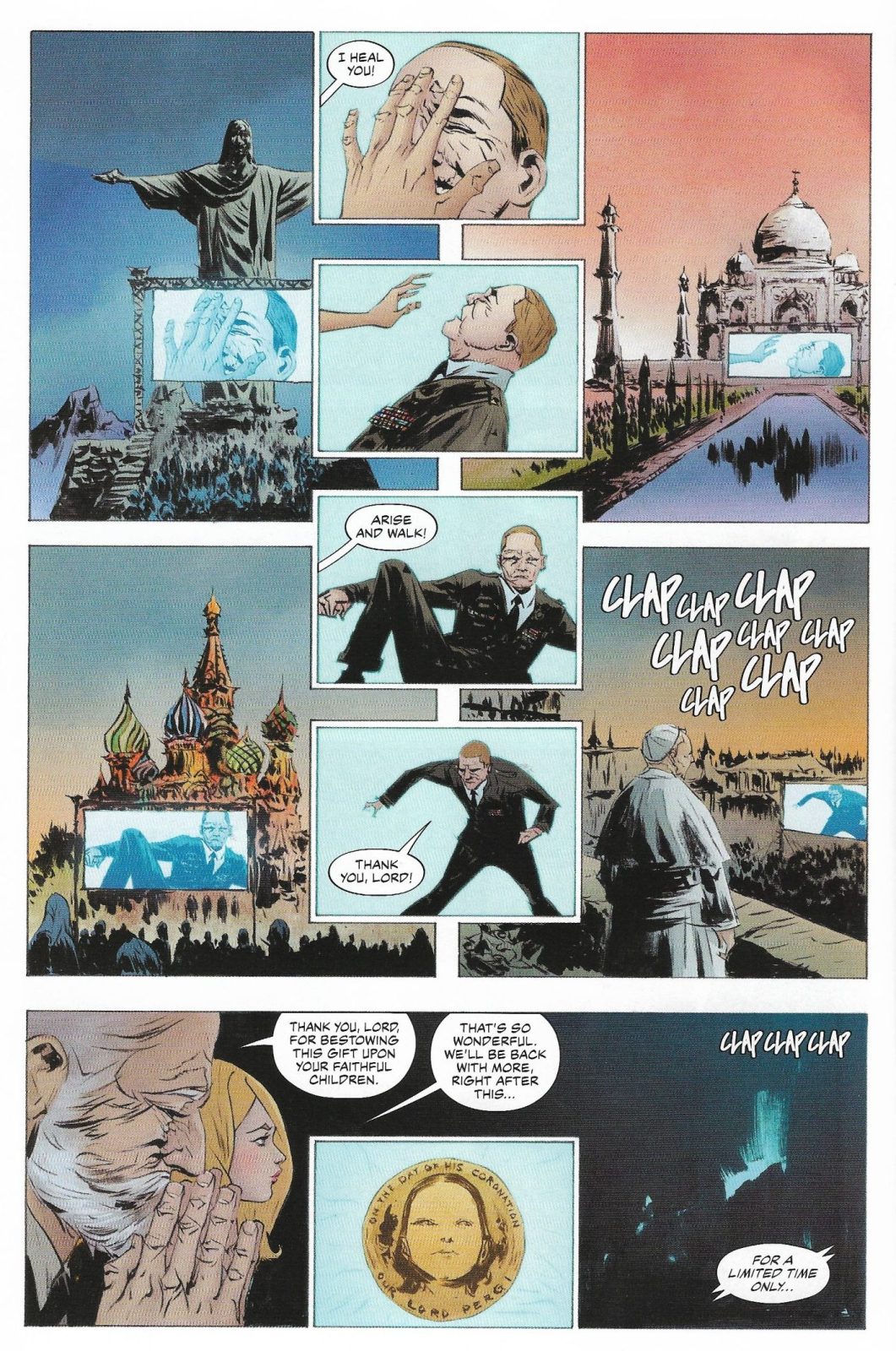

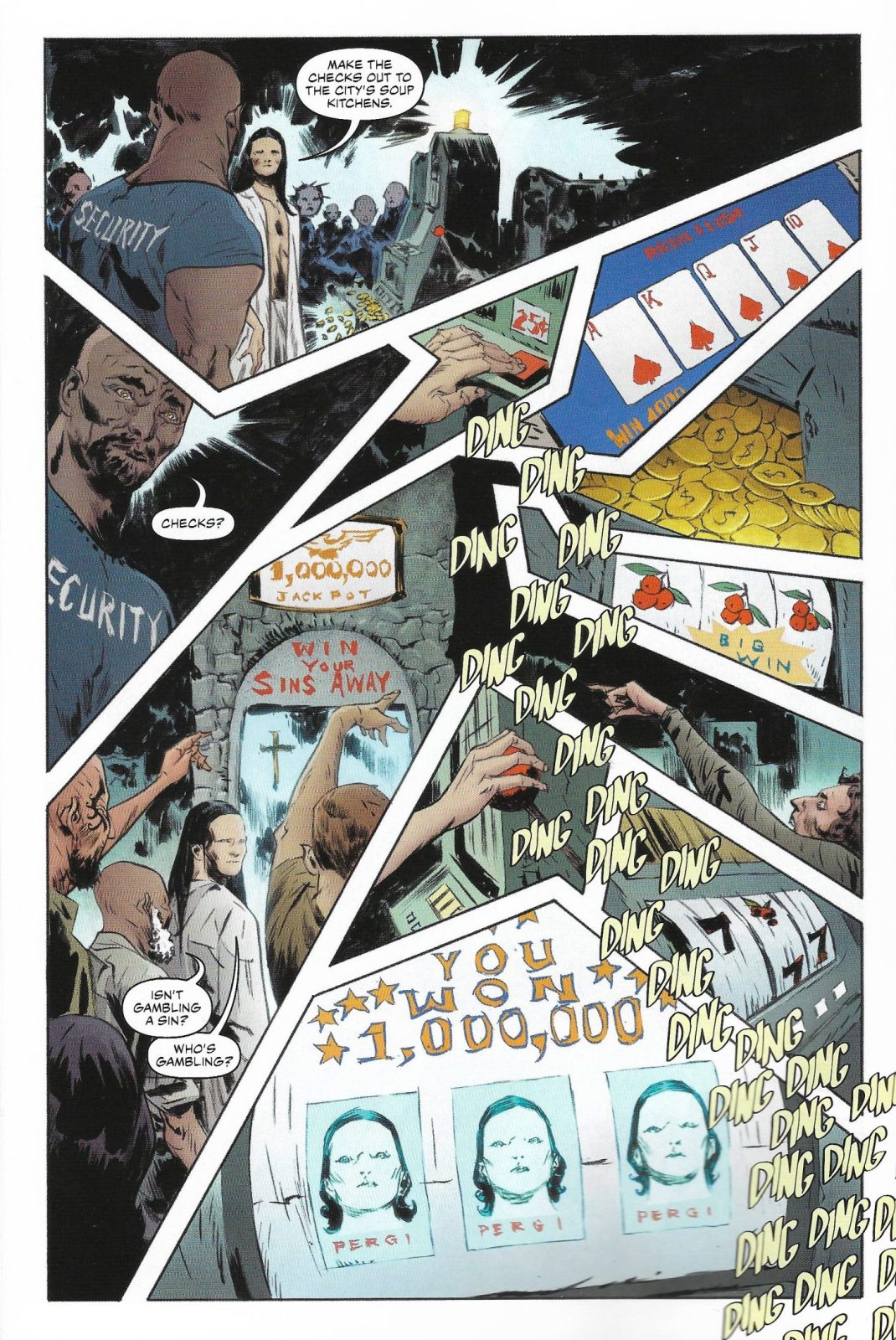

Nutshell elevator pitch for Seven Sons is a pretty decent hook: there’s a Second Coming afoot, built on a magic prophecy written in the birth of seven identical children to different mothers across the planet on July 7th, 1977. If it seems too good to be true, you shouldn’t be surprised to hear the whole thing was a scam concocted by mad science. Problems compound when an actual resurrection occurs in the midst of all the vigorous fakery. Cue hijinks.

Despite the heady high concept, this is a fairly action-packed story - there are shoot-outs in nightclubs, ambushes in train stations, and car chases. Pick up issue #4, flip to the middle of the book. Our hero Delph, the only one of the titular Sons with a lick of a clue, jumps into a car for the purpose of escaping from the church’s armed thugs, sent to find their missing Messiah. Only problem is, Delph has never driven before, so he manages to crash the car off the side of a mountain.

I’m struck by how kinetic this sequence reads. How remarkably clever - every time the action heats up the panels splinter and crack. The regular square grids utilized for flashback and exposition give way to kaleidoscopic chaos. Like someone took a hammer to the page and drew around the shards of glass. It shouldn’t work. It should be incredibly annoying. And yet it reads just fine. Zips along. Can’t imagine this working for most anyone else.

As religious satire goes, Seven Sons has more bite than many, if still not enough to truly sting. I think it pulls punches in the last act to set up a sequel, unless the ending was meant to be a non sequitur. In any event, the finale lands a little bit flat because of it, even if most of the story hums right along. We see throughout that the ends of religious faith wedded to epistemological certainty are warrantless atrocity. We see that in the way every other aspect of life in the United States has been brushed to the side with absolutely no fucks given. There’s no more room for other religions and most of the stuff they teach in school.

There’s another essay that could be written on the position of Islam in this text. I’m really not the one to write it. There was some good with the bad, even as I don’t know if it works as well as the writers want it to. Of course, Islamic radicals are the main dissenting voice in this world. The story asks us to believe that the Seven Sons scheme was convincing enough to wrench the whole of civilization off its axis, in favor of breathless anticipation of a Messiah who promises to arrive via pay-per-view. The aforementioned Islamic radicals committed to putting an end to this wildly blasphemous scheme can’t but be seen in a heroic light, as among the very few people shown to have retained their original religious affiliation in the face of the encroaching event. Certainly not given the context of the entire world having fallen into the clutches of a plainly dubious money-making scheme.

That’s the nightmare wrapped around the heart of this story - things just start to fall apart once a sufficient percentage of the population gives a fuck about nothing but the end of the world. Sounds a bit familiar. To the book’s credit it doesn’t really hinge on whether or not the revelation of the Messiah’s origins in forbidden science would move the needle, not in a world committed to following the Seventh Son as their new Deity. It would be something they could spin very easily to people who wanted to believe whatever they had to say. It probably wouldn’t move the needle at all. No one would care all that much if the end product was the Second Coming. See? The ends justify believing any old lie, until you’re waist-deep in blood. The principle still applies if, especially if, you assume the persons at hand stood to make a lot of money.

Did this story begin life as a screenplay? One could, if feeling ungenerous, perhaps discern the outline of a cinematic treatment that could have resulted in something vaguely reminiscent of The Da Vinci Code - what with the vast religious conspiracy at the heart of a mystery film with a handful of action set pieces. To its, credit the book is a bit more cynical about religion than much of mass media tends to be now, even if it does end on with advent of an actual Second Coming to supersede the venality of the ersatz Messiah. Possibly also scientifically motivated? The ending is ambiguous.

At its best, the story reminded me of another film from long ago, The Rapture. Mimi Rogers vehicle - one of the scariest movies I’ve ever seen in my life, despite being in no way a horror movie. Takes the idea of a Second Coming very seriously, real woozy end-of-days feel to it. Pre-millennial tension up the wazoo.

Well, it’s officially the post-millennia and, surprise, things are still kind of tense. As far as religious conspiracy media goes, this one had more thought to it put into than most. Very much a story of the moment, for better and for worse. But - not merely a story. The fact is that if this were a movie I’d almost certainly never see it. Seven Sons is not a movie, it is a comic book drawn by the ineffable Jae Lee. I’ve sat here and given serious thought to the world of this book and the creatures within it only because it was drawn by Lee, at the pinnacle of his powers, composing each panel and page with meticulous attention to balance with no substitution of detail. My friends - Jae Lee hasn’t missed a beat. He’s never stopped getting better, even if I will confess to missing some of the striking bold use of black ink that defined his early pages. He squeezed so much juice out of silhouettes.

Ahhh, don’t get me started. I could talk about Jae Lee all day. He started out with a lot of Sienkiewicz before becoming something completely different. Of course, The Sink knows a thing or two about starting off with a strong understanding of another artist’s style before branching out. There’s no mistaking Lee’s work for anyone else now; truly breathtaking.