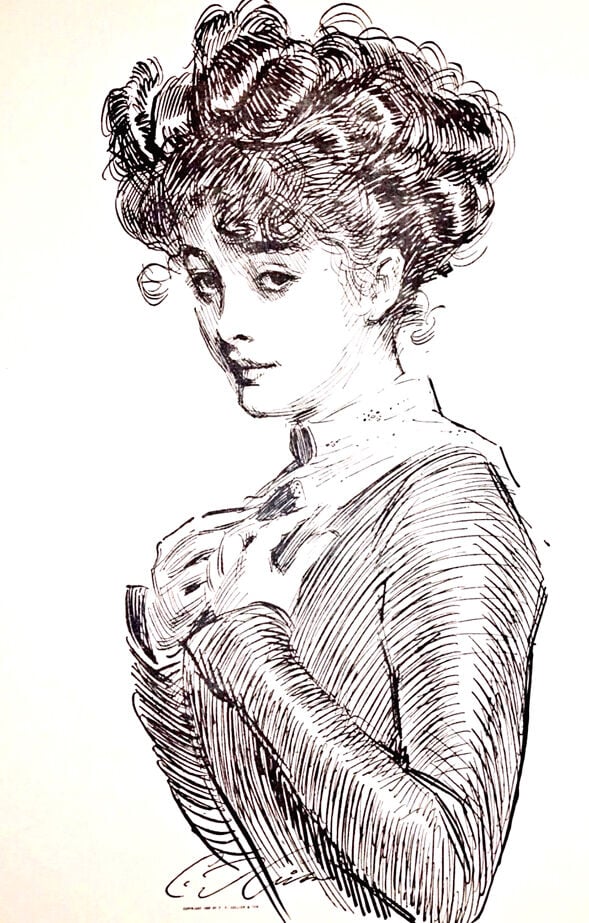

Charles Dana Gibson was the most popular American illustrator at the turn of the 20th century and his drawings informed fashion, culture and social commentary of the time.

His family moved from Boston to Flushing when he was a child and he grew up on 149th Street, attending Flushing High School, back when the town was rural, “with woods, water and plenty of open spaces,” his 1944 New York Times obituary reads.

Now, the Queens Historical Society is featuring an exhibit, “Charles Dana Gibson: The American Trendsetter,” with prints, photographs and rare books of his illustrations, highlighting his legacy and connection to Queens.

“When he was starting his career at the turn of the century, New York was undergoing this amazing transformation,” said Paula Uruburu, a professor at Hofstra University and author of “American Eve.”

“You had this explosion of everything that was going on culturally and economically and New York was the center of it,” said Uruburu, who was born in Queens Village.

Gibson trained under sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens and attended the Art Students League in New York City. He was hired for his satirical depictions of upper-middle-class life for magazines like Life, Collier’s Weekly and Harper’s Weekly.

“One theme he illustrated was making fun of the upper class and people trying to climb the social ladder,” said Jeran Halfpap, education and outreach coordinator at the Queens Historical Society. “He’ll illustrate the relationship between men and women. He liked to joke that men are the weaker sex and that they’re slaves to their emotions.”

Uruburu’s book tells the story of model Evelyn Nesbit, the most sought-after model of the Gilded Age. Nesbit became the face of the “Gibson Girl,” Charles Dana Gibson’s embodiment of the “New Woman.”

She was discovered by famed architect Stanford White, whose commissions included Madison Square Garden. White insisted that she only model for the best, starting with Gibson. Gibson’s wife, Irene Langhorne, was the original muse for the Gibson Girl before Nesbit.

The Gibson Girls played sports, rode bicycles and did what “liberated, independent women could do,” said Uruburu. They were tall, athletic and beautiful. Gibson’s obituary described her as “pretty in all her Victorian furbelows, attractive, a trifle arrogant and aloof.”

“We see them as being cultured and educated and not the mousy Victorian types,” she said, “The Gibson Girl was breaking all those rules from the past.”

Gibson’s iconic pen-and-ink drawings include “The Eternal Question,” depicting a woman on the cusp of adulthood. Once a girl turned 16, she would traditionally tie her hair back. But some locks still fall in the picture, with one in the shape of a question mark, begging the question “what does a woman want?” explained Uruburu. “It perfectly captures what Gibson was doing and what was happening in New York at the time,” she said. “It’s like this transition between the old world and the new world.”

Although progressive for the time, Uruburu points out that it was still an “elitist” point of view. “There are no people of color, there’s just this very rare group of young, beautiful and almost always rich women.”

Gibson had the power to set the social attitude of the time as Collier’s Weekly was read by people with money, said Halfpap. His ideals and style lived on through the 1920s, setting the stage for the flapper trends to come. Gibson proved himself as a painter later in life and even held stake in Life magazine for a time.

The exhibit will be on through November at the Queens Historical Society’s Kingsland Homestead location. Visits may be booked in advance on the QHS website.

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.