On this day thirty-eight years ago saboteurs bombed Greenpeace’s flagship in Auckland’s Waitematā harbour, killing a crew member.

By Frances Walsh | 10 July 2023

Shortly before midnight on 10 July 1985 Rainbow Warrior sank within minutes of explosions ripping through its hull while berthed at Marsden Wharf. French secret agents had planted two limpet mines, one near the propeller, the other on the outer wall of the engine room. Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira was retrieving equipment below deck when the second mine was detonated, and was knocked unconscious and drowned.

At the time Rainbow Warrior was about to lead a flotilla of vessels to the isolated Moruroa Atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago in Mā’ohi Nui (French Polynesia), to protest atmospheric atomic tests conducted there by the French since 1966. ‘It’s beautiful,’ said President Charles de Gaulle, who was present at one of the first tests; as the azure sky flashed bright orange, the towering radioactive cloud mushroomed, the water was sucked out of the lagoon, the coconut trees bent low as the force of the bomb hit, the dead fish and molluscs rained down, and radioactive fallout was borne on the winds, across a vast swath of Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa.

Before France’s act of state-terrorism and the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior, Indigenous activists, peace groups, and governments had long opposed nuclear testing in the Pacific. The Atom (Against Testing on Moruroa) committee, for example, formed in Fiji in 1970, to educate the public about the dangers of radioactive fallout, and on the nature of colonisation. In the same decade Anglican priest Walter Lini—Vanuatu’s first prime minister— coined the term ‘nuclearism’ (combining the words nuclear and colonialism) when strenuously opposing French but also British and American nuclear tests in the Pacific; in the 1950s the latter two countries had tested nuclear weapons in Kiribati and the Marshall Islands respectively.

In 1973 the New Zealand and Australian governments took France to the International Court of Justice: the French government ignored the court’s ruling to halt testing during proceedings and the NZ government dispatched two navy frigates—HMNZS Canterbury and Otago to Moruroa to protest for a nuclear-free Pacific. A flotilla of civilian yachts was also involved in the action, including Vega (aka Greenpeace III) currently berthed at the New Zealand Maritime Museum. Skippered by David McTaggart and crewed by Anna Horne, Nigel Ingram and Mary Lornie, the ketch was boarded by French commandoes near Moruroa. Their assault of McTaggart and Ingram was photographed by Horne, who was to hide her film where the sun don’t shine to avoid its detection. News of the violent incident made international headlines sparking further criticism of the testing programme. Succumbing to pressure, and after 41 tests, the French abandoned atmospheric testing in Moruroa in 1974. They then commenced underground testing.

Rainbow Warrior was in Auckland in 1985 as part of a six-month Pacific peace voyage. The ship had come from the Marshall Islands where it had relocated 300 people from Rongelap Atoll to the island of Mejato 180 kilometres away. The islanders had previously asked the US government to help moving them to an uncontaminated new home, to no avail. In 1954 the US had detonated a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb called Bravo on Bikini Atoll, just 120kms from Rongelap, where residents thought the ash falling from the sky was snow. The US went onto conduct another 23 nuclear tests on Bikini before calling a halt in 1958, by which time high incidences of cancer—particularly of the thyroid—were evident among the Marshallese and the incidence of stillbirths and miscarriages among Rongelap women was more than twice the rate of Marshallese women who hadn’t been exposed to radiation.

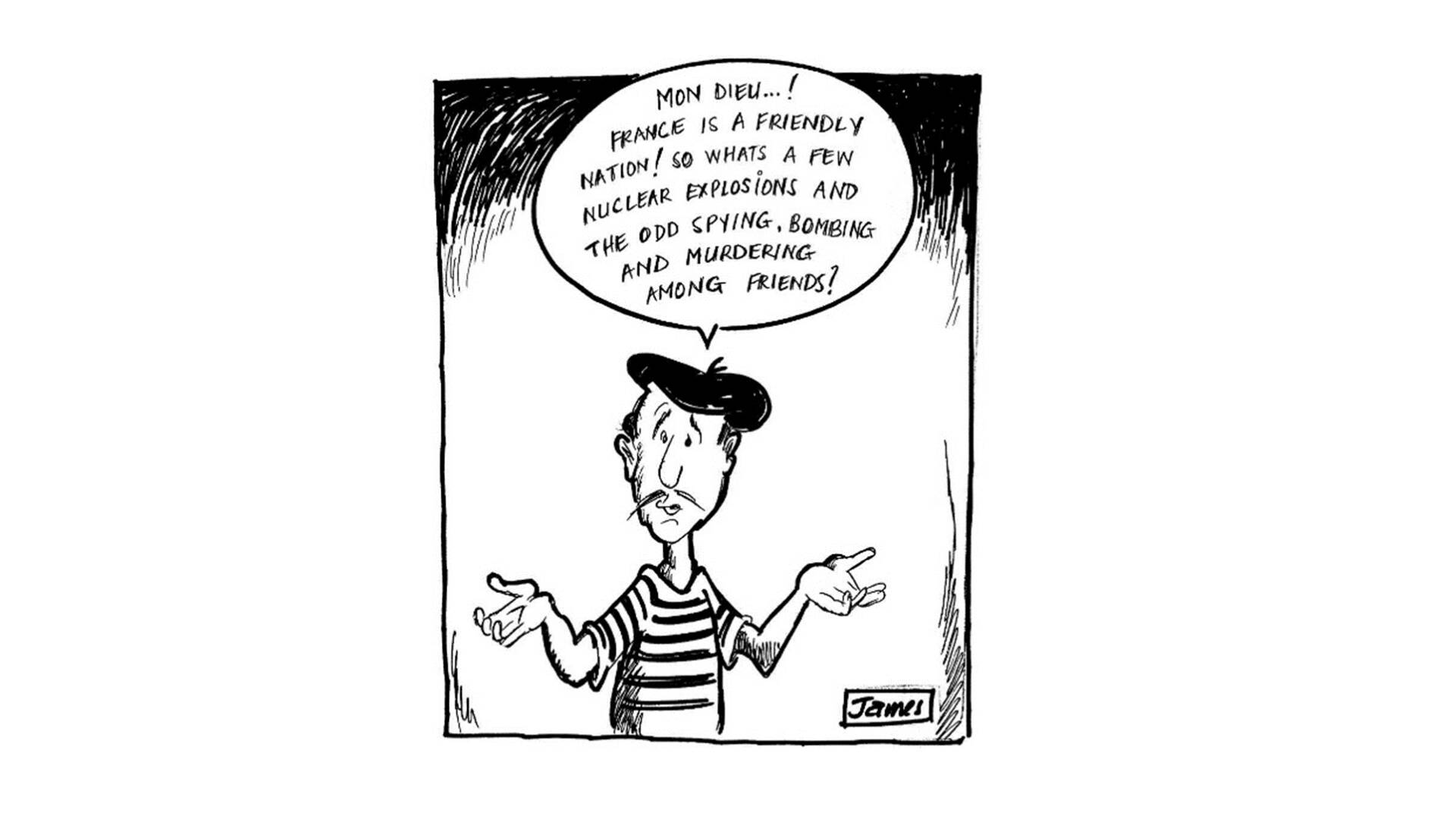

By the time Rainbow Warrior had sailed into Auckland to take in supplies and meet up with a flotilla heading for Moruroa, the French secret service were well into Opération Satanique”, their mission to sink Greenpeace’s flagship. Following the bombing a local police investigation unmasked two of the secret agents, Major Alain Mafart and Captain Dominique Prieur; the French Government eventually admitted that the saboteurs had bombed Rainbow Warrior and were acting on orders. Cue a deluge of new members for Greenpeace, general outrage, and black humour from cartoonist Jim Lynch whose work directly below appeared in the Taranaki Daily News on 2 September 1985.