When Dorothea Lange found out that her famous photograph, “Migrant Mother”—the iconic image of one exhausted woman and three kids living in misery, which has come to visually represent the Great Depression—hadn’t yet been included in her upcoming career retrospective at MoMA, she simply said: “It’d be alright with me to leave her out.” Lange died three months before the show opened in January 1966, but she had full involvement in its curation, from her home studio in Berkeley, while battling terminal cancer. By then the picture, often cited as a genre-defining image of photojournalism, was already world-famous, to the extent that Lange was somewhat uncomfortable with its ubiquity—she’d taken it on commission from the US government, so she didn’t own it (which is why it’s been on coffee mugs, postage stamps, t-shirts).

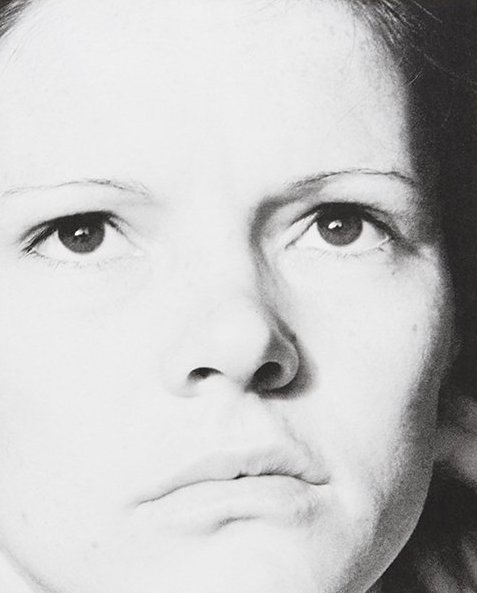

Photographer Sam Contis’s latest project challenges this reduction of Lange’s career to one particular kind of photography. Her new book, Day Sleeper, presents previously-unseen work from Lange’s archive which Contis found, cropped and arranged: what emerges is what she calls Lange’s “everyday” work, with photographs of her family (the boy on the cover is her then-five-year-old son, Dan, in 1930), nature, and, yes, a lot of idle people taking naps. There are photographs of the desolate California of the Depression and the post-war period, but also pictures taken in the streets of San Francisco and the East Bay, and traditional portraits: it turns out that Lange owned the best portrait studio in town (and a real hangout spot for artists) for ten years. The work she is celebrated for, which she famously made on assignment for the Farm Security Administration, represents only four years of a four-decade career. Some of Day Sleeper’s photographs are exhibited at MoMA’s Words & Pictures show, the museum’s first retrospective of Lange’s work since the 1966 event.

Like Lange, Contis moved to the Bay Area after spending much of her twenties around New York. Her own work feels very zeitgeisty—her previous book, Deep Springs, was concerned with hypermasculinity and the iconography of the American West through looking at an isolated ranch-cum-college town for young men in Sierra Nevada, and work from that project is featured in the Barbican show Masculinities: Liberation Through Photography. Her pictures are deceivingly quiet, but presented together generate a restlessness, an almost mythical angst, sometimes a latent violence. (Incidentally, it is her picture on the cover of Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous).

From Daysleepers, courtesy MACK.

From Daysleepers, courtesy MACK.

Like Lange, Contis is fascinated by textures, human skin, fragments of bodies, close-ups; hands appears in both artists’ work over and over again, as if they’re convinced it is they, not the proverbial eyes, that hold clues to the soul. Both share a visible sense of desire in the way they look at the world, what Contis calls over the phone a “need to get up close,” and an “interest in the surface of the body and the way the landscape imprints itself on it, as well as the way the body is reflected in the land.”

It was personal curiosity that led Contis to immerse herself in the more than 40,000 negatives, contact sheets, field notes and letters by Lange collected at the Oakland Museum of California, upon learning that the archive was only a couple of miles from her house. She soon began to take iPhone pictures of the photos to print them out and spend more time with them at home: “The archives were not open long enough to accommodate me,” she laughs. “Eventually my studio became four walls floor-to-ceiling of Dorothea Lange, and I realized that what I was doing was seeing through her. I wasn’t going out into the world and making pictures, but I was looking at the world through what she had left behind, and I was also seeing things that I would have been attracted to in my own practice—it became this sort of double seeing,” says Contis. One can see Lange move through the world in her contact sheets, allowing people to notice her and slowly getting closer to them. Contis shares a similar kind of relationship with her subjects: “I want to be seen first. Then I want to be forgotten.”

From Daysleepers, courtesy MACK.

From Daysleepers, courtesy MACK.

Day Sleeper is organized in a series of sequences in which Contis has loosened the images from their original context, moving back and forth between decades, allowing new meaning to emerge via the new arrangements. In one of the sequences, balloons become a pregnant belly becomes an oval doorway becomes round glasses becomes a small bowl surrounded by flowers, and on it goes; though to pin it down into a single aesthetic motif would be unfair. While sequencing, Contis was thinking about language, a famous preoccupation of Lange’s, but in Day Sleeper, the only text—a brief essay and quotations—is at the very end. Instead, she inserts air, white space for the reader to insert their own meaning, alongside black palate-cleansing pages. The shapes and forms relate to language, but often not in a direct, one-to-one literal way: they feel closer to echoes reverberating. “The book slows you,” Contis says. You have to sit with each image. “I wanted you to be aware of the act of looking.”

“The way we look at documentary work is often in a chronological way, and that can give us a feeling of looking back into a fixed or distant past, but I wanted these pictures to feel closer and more immediate,” she adds. By moving away from that kind of presentation, Contis felt she was able to have a conversation with Lange and her work across a whole lifetime, make the archive come alive

From Daysleepers, courtesy MACK.

From Daysleepers, courtesy MACK.

Day Sleeper forces an act of looking that is obviously at odds with not only our habits of attention, but our current ways of engaging with photography itself. That aforementioned “second looking” became a way for Contis to explore what she calls the inherent subjectivity of seeing: “It’s so hard to ever be fully objective in this medium, and Lange understood that inherently, which is why she struggled with the terms documentary and journalism.”

The co-authored book is a meaningful reminder of how the archive can be an active, alive channel for two artists to communicate across time, which becomes especially urgent when redressing erasures and misinterpretations. Contis deliberately interweaves the personal and the political, making the argument that politics informed every single part of Lange’s life, and that her personal work richly influenced the photojournalism (there are several pictures in Day Sleeper where her subjects raise their hands up to their mouths in a gesture similar to that of Florence Owens Thompson, or ”Migrant Mother”).

Lange eventually accepted the inclusion of her most famous picture in the retrospective (at the desperate insistence of the curator, John Szarkowski), ceding in the end that it did, indeed, “belong to the public” but asking that it be put “in some relationship, in a context that people don’t expect, give her a new both interpretation and understanding.” Contis is, in some ways, picking up where Lange left off. In a letter Lange wrote in the late 1950s, she seemed to lay down the instructions: “I find that it has become instinctual, habitual, necessary to group photographs. I used to think in terms of single photographs. The bull’s eye technique. No more. A photographic statement is what I now reach for. Therefore these pairs, like a sentence of two words. Here, we can express the relationships, equivalents, progressions, contradictions, positives and negatives, etc. Our medium is peculiarly cured for this. (I’m just beginning to understand it.)”